Migraine is a neurological disorder, experienced by more than 25% of women during the course of their lives. It causes headaches, of course, but headache is only part of it. Migraine makes it difficult for people to concentrate, to work, to meet friends, to carry on any of the normal activities of daily life. So if you suffer from headaches bad enough to stop you doing what you want to do, you have migraine. If you suffer from headaches that make you feel sick, you have migraine. If you suffer from headaches that are made worse by light, or noise, or movement, you have migraine. If you get headaches with your periods, or when you eat a Chinese takeaway, or when you overindulge, or when you sleep in, you have migraine.

The name ‘migraine’ originally comes from the Greek word hemicrania, meaning ‘half of the head’. It is true that migraines sometimes affect only one side of the head, but often the pain is bilateral, at the front or the back of the head, or in the neck; more rarely in the face, and rarer still in the body. It is generally throbbing in nature, and made worse by even modest exertion. Most migraine attacks are severe. Untreated, they can last hours, or even days at a time. The pain of migraine is typically accompanied by other features such as nausea, dizziness, sensitivity to lights, noises, and smells, lack of appetite, and disturbances of bowel function.

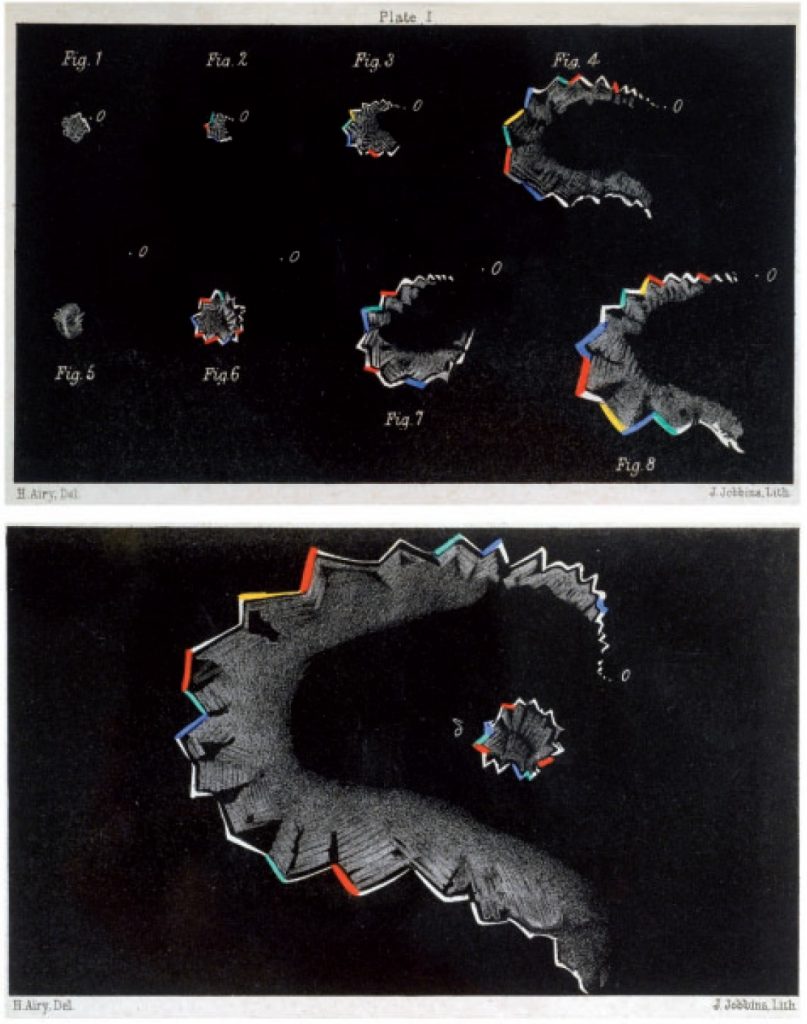

About 20% of migraine sufferers experience aura, usually before the headache starts. Most aura is visual, consisting of a combination of positive phenomena (often moving or expanding zig-zag patterns) and negative phenomena (blind spots).

A similar proportion of migraine attacks produce warning symptoms up to 48 hours before they start. These symptoms include fatigue or abnormal bursts of energy, neck stiffness, yawning, or frequent urination.

What causes migraine?

The tendency to suffer from migraine has a genetic basis, but individual attacks may be triggered by internal or external influences, or simply come by themselves for no specific reason. Common triggers include stress, sleep disturbances, missing meals, alcohol, strong odours, changes in the weather and, for women in particular, hormonal fluctuations. The most common hormonal trigger is the steep fall in oestrogen that occurs immediately before periods; hence, many women experience attacks at the start of, or just before, their periods.

Why do migraines get worse around the menopause?

Although migraine affects both sexes, it is predominantly a female disorder, affecting 43% of women and 18% of men over the course of a lifetime. Thus, migraine rates are identical in boys and girls, but following puberty the prevalence increases more in women than in men; by their 30s, women are three times more likely to experience migraines than men. Perimenopause further increases the risk of migraine. The huge American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) study published data in 2016 showing that migraine was 40% more common in perimenopausal women than in younger women. Several studies show that about 30% of women attending menopause clinics have migraine, most reporting severe attacks at least monthly.

The increase in frequency and severity of migraine attacks in the perimenopause is partly because menstrual periods may be more frequent, and partly because greater fluctuations in hormonal levels at this time of life (higher oestrogen and lower progesterone) disrupt the menstrual cycle. These changes particularly impact on women whose migraines previously tended to come with hormonal changes. Following menopause, the prevalence of migraine gradually improves with time, mirroring the underlying decline in ovarian function.

How can migraines be tamed?

There are three ways to treat migraine: lifestyle and trigger management, acute treatments (painkillers taken during attacks), and preventive treatments (medication or other interventions that reduce the tendency to have attacks).

Migraine likes people to be boring! A regular regimen of meals, hydration, sleep, and stress is always helpful in reducing the tendency to migraines; recognising this is straightforward, but actually making the requisite changes in a modern busy life may be more difficult.

Some form of painkiller is usually needed. If simple painkillers such as paracetamol, aspirin, or ibuprofen are not effective, then you should ask your GP to prescribe a triptan (a specific migraine drugs such as sumatriptan (Imigran)). Opiates (codeine, tramadol, and so on) must be avoided.

Preventive treatment is prescribed when headaches significantly interfere with work, study, or social life. Typical preventives include old-fashioned tricyclic antidepressants, such as amitriptyline (taken in low doses); medications that reduce blood pressure, such as beta-blockers (e.g. propranolol) or candesartan; and epilepsy drugs, such as topiramate or sodium valproate.

What about HRT?

Taking oestrogens continuously can benefit migraines, particularly in women whose migraines are set off by falling oestrogen levels. In contrast to contraceptive doses of oestrogens, which are contraindicated in women with migraine with aura, physiological doses of natural oestrogens can be used in such cases. Using only the lowest dose oestrogen patch necessary to control the vasomotor symptoms of menopause (hot flushes, night sweats, and so on) minimizes the risk of unwanted side effects. Cyclical progestogens can have an adverse effect on migraines, so continuous progestogens, as provided by the Mirena coil, or in continuous combined HRT patches, are preferable. It is impossible to predict ahead of time, however, whether any particular hormonal intervention will be helpful.

If drugs fail, interventions such as greater occipital nerve blocks or Botox can be tried. New non-invasive neurostimulation techniques such as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and vagal nerve stimulation (VNS) may also be helpful. New options are becoming available, most notably the CGRP antibodies such as erenumab (Aimovig), monthly preventive injections that target the specific neurotransmitters that cause the problem. Overall, these are exciting times for the treatment of migraine.

ABOUT THE SUBJECT EXPERT:

Dr Mark Weatherall is a Consultant Neurologist at Stoke Mandeville Hospital in Buckinghamshire, UK, Vice-Chair of the British Association for the Study of Headache and a former Trustee of The Migraine Trust. He was a highly regarded historian of medicine before studying clinical medicine at Cambridge. Junior medical jobs followed in Cambridge, London and Oxford, before he completed his specialist training in neurology in the North-West of England. He spent twelve months as a clinical research fellow with Professor Peter Goadsby and Dr Holger Kaube of the Headache Group at the Institute of Neurology in London. He is a Fellow of the Royal Colleges of Physicians of London and Edinburgh.

His interests include the diagnosis and management of chronic migraine, facial pain, visual snow and secondary headaches associated with systemic disorders, as well as the historical, social and cultural aspects of headache disorders. He has made presentations on these subjects at recent meetings of the International Headache Society, the European Headache Federation, the Migraine Trust International Symposium, and the Association of British Neurologists. He actively promotes the importance of headache disorders through social media such as Twitter (@weatherallmw), and more traditional media platforms, and via www.londonheadachecentre.co.uk